* Blog originally written August, 2017

Reflections on my Secondment in Wales

What becomes possible when we admit to not-knowing? In my research on “imaginitive leadership,” a golden thread throughout my conversations with artists, creative practitioners, culture shifters, and innovators here in Wales has been their certainty about the urgent need to embrace uncertainty.

Committed to the Well-Being of Future Generations

To set the stage, there is reasonable certainty that Wales is publicly committed to supporting social and ecological sustainability. In 2015 the government passed a landmark piece of legislation called The Well-being of Future Generations Act, which includes a central mandate to put sustainable development principles at the core of all government policy and government supported activities. The second goal of this leading-edge national policy is ‘A Resilient Wales – A nation which maintains and enhances a biodiverse natural environment with healthy functioning ecosystems that support social, economic and ecological resilience and the capacity to adapt to change (for example, climate change).’ The United Nations has said that “What Wales is doing today the world will do tomorrow” .The Future Generations Act has generated a lot of possibility and expectation, but also a lot of doubt and fear of failing to deliver on the promise.

A Universal Experience of Uncertainty

As I have been seconded with the Welsh Government and the Sustainable Places Research Institute, a common refrain in discussions and interviews has been that everyone supports the idea, and no one knows how to get there, or even what it really looks like in practice. At the same time, Brexit is looming on the horizon with its threat to funding streams and economic stability, especially in the heavily subsidized rural regions of Wales. Climate change and declining ecosystem resilience (marked by biodiversity loss and increasing flood risks) increase the potential for concomitant economic and social de-stabilization. Political, economic, and ecological risks all put the livelihoods and well-being of people in jeopardy. Sound familiar? While the details of the Welsh context are unique, this situation mirrors the dilemmas people are facing around the world – a desire to become a just and ecological civilization, a sense of urgency, and a murky path forward.

Imperative to Escape the Gravitational Pull of Inertia

On the bright side, the immediacy of such uncertainty, with the added weight of political mandates and necessity for compliance, engenders an urgency for experimental approaches and incentives to escape the inertia of “how things are done.” In conversations with artists, community leaders, and individuals within the government (both management and frontline staff), the importance being comfortable and open about “not knowing” has been brought up again and again. Admitting to not knowing and inviting dialogue and experimentation can be understood as a generative and attractive way to bring people together in new conversations and for new innovative collaborations. In cultures that are typically risk-adverse and in institutional structures that have unintentional counter-incentives for trying new things (a commonly recognized challenge in governmental institutions), an urgency towards experimentation can open up opportunities for establishing new norms, new ways of working, and new cultural narratives. Many people I interviewed have said that by starting from a place of “not knowing” they were able to establish unlikely coalitions and collaborations, that they personally felt more honest and authentic and confident (without having to pretend to know the answers), and that participants felt empowered to contribute new ideas and perspectives.

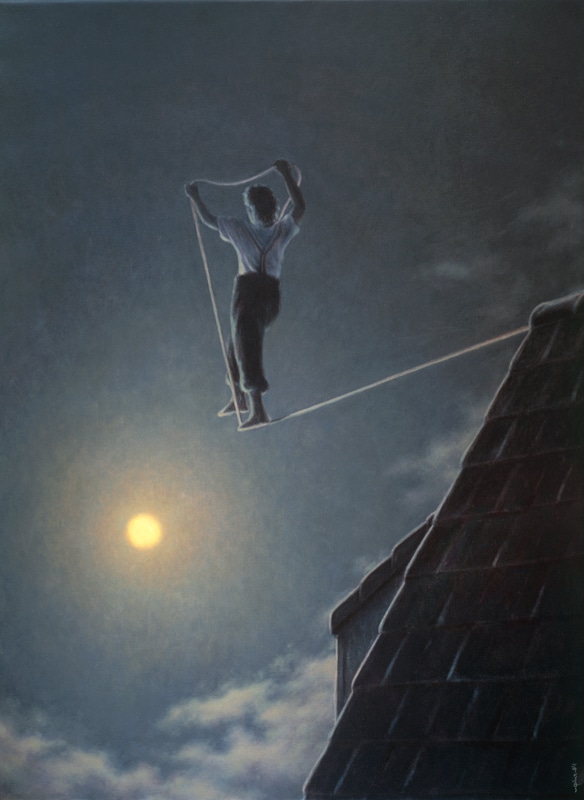

Welsh Artists Creating Containers for Not-Knowing

My research focuses on the role of creative interventions and “imaginative leadership” in supporting transformative capacity. Socially and ecologically engaged artists often focus on setting a social container for “not-knowing,” for evoking environments of experimentation, and for designing creative strategies for disrupting habituated forms of thinking. Perhaps in a context defined by “art”, knowing is not the standard currency of authority and/or the behavioral norm. The question for the next stages of my research with the Welsh Government has been: how can art and arts based practices contribute in the context of planning, project development, and establishing new “co-productive” ways of working? This fall I co-designed and conducted workshops with the Welsh Government and artist Fern Smith that used arts-based practices to intentionally experiment with “not knowing” and to play with new perspectives of time, the role of nature as a partner in co-production, and ways of conceptualizing and communicating about the relationship between Natural Resource Wales, local communities, and the natural environment. Stay tuned for a follow-up blog post that summarizes the events!

Inspiration from the Creative Sector:

Check out the following for some interesting ways artists are engaging here in Wales:

Fern Smith: http://www.emergence-uk.org/

Emily Hinshelwood: http://emily-hinshelwood.co.uk/three-questions-about-climate-change/

Emma Price: http://www.studio-response.com/

Larks and Ravens: https://larksandravens.com/

Stephen Hodge: http://www.mis-guide.com/ (Exeter, UK)

Pip Woolf: https://woollenline.wordpress.com/