This is the second blog in a series that reflect on the SUSPLACE Final Event that was held from May 8 -10, 2019 held in Tampere, Finland. The event addressed the theme of ‘Exploring Places and Practices through Transformative Methods’. To harvest knowledge and outcomes, we asked some participants to write a short blog post capturing their experiences. Find below the blog, written by Emily Finney, team leader Strategic Initiatives at the Welsh Government, addressing the role of policy.

Delivering regenerative development and transformational change through people and place: a blog from a policy perspective

By Emily Finney, team leader Strategic Initiatives at the Welsh Government

The scene is set. We are running out of time. The quadruple squeeze – population growth, ecosystem degradation, climate change and the added element of surprise – demands urgent and transformational change. Yet, with an increasingly polarised societal debate, how do we manage change in a way that brings societies together and for people and communities to be more empowered to determine their own futures?

My role in policy development is about drawing on a wide range of evidence to develop ideas and options to effect change, for decision makers. In Wales, strong foundations for regenerative development and place based approaches have been enacted into primary legislation through the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 and the Environment (Wales) Act 2016. This includes national priorities which have been set to

- Deliver nature based solutions and circular economy approaches, and

- Take a place based approach

across public service delivery and through governance structures which facilitate collaborative working more widely across the private sector, civil society groups and individuals. [See Annex for more details on the policy approach in Wales].

SUSPLACE’s approach – enhancing sustainable pathways at a place-based level – is about discovering and facilitating processes of change that build on the resources and capabilities of people in their context. The conference provided a powerful range of practices and approaches to support delivery for lasting, transformational change. Drawing from the conference themes; disruptive and creative methods; engaging people and ethical doings were three recurring narratives behind the practice of place making:

Time, Space and Essence

These underpin the elements of place-based governance

- Local leadership

- Learning together

- Strong networks

- Information sharing

- Diverse engagement.

Creating space

Place can be imaged or a state of mind, and practices give the ability to respond to the future, providing a platform to push for innovation, transformation and regenerative approaches to social and ecological systems. Those covered at the conference were both broad and deep, ranging from personal actions, building on what already works through appreciative inquiry, and through a range of experimental, disruptive and creative methods.

From a policy perspective, with the future highly uncertain- both from a social and ecological perspective – we need to create space and delivery structures to enable a diverse range of approaches and pathways towards a sustainable future; to ‘learn by doing’. In the words of C.S. Holling ‘The only way to approach such a period in which uncertainty is high and one cannot predict what the future holds is not to predict but to experiment and act inventively and exuberantly via diverse adventures in living’. In turn, this means creating space to take risks, explore disruptive new approaches and well as building on what works, and to share the learning from both successes and failures.

Time and Essence

Collaboration across sectors, disciplines and within communities is at the heart of place making. Collaboration requires key roles and structures to be put in place to build networks, link the very local to the wider system in which they work, and facilitate dialogue. But it is more than that. It requires working at the level of what it means to be human, our ‘essence’; our need for meaning, purpose and to be understood; sense of the wonder of nature; and the potential and energy within us all. Throughout the conference, creating time to develop a deep understanding of other’s needs, values and knowledge was seen as fundamental.

From a policy perspective, building time and capacity within delivery structures and programmes to enable relationships based on meaningful purpose, trust, respect and working with the energy of individuals is vital for lasting change and building social capital. This requires resource and commitment.

Practices and approaches

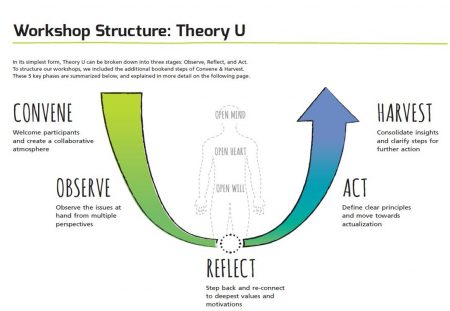

Otto Scharmer’s Theory U is a change management approach used throughout many of the studies at the conference. The process has three key elements

- A framework for seeing the blind spot of leadership and systems change

- A method for implementing awareness-based change, processes, principles and practices

- A new narrative for evolutionary societal change, updating our mental and institutional operating systems in all of society’s sectors.

The principles behind Theory U are about breaking past unproductive patterns of behaviour and decision making through 7 leadership capacities when looking for solutions to problems:

- Holding the space: listen to oneself, to others and make sure that there is space where people can talk

- Observing: observe without your voice of judgment

- Sensing: Connect with your heart

- Presencing: Connect to the deepest source of your self.

- Crystallizing: Access the power of intention

- Prototyping: Integrating head, heart, and hand

- Performing

In his keynote speech on Day 1, Bill Reed spoke about his approach to regenerative development and design. His framework for engagement explored how information is retained through different paradigms of engagement ranging from ‘tell’ to reflective approaches based on ‘essence to essence’ engagement, consistency and field building for lasting capacity. He explored the extent of the ambition and the use of language around sustainable, restorative and regenerative approaches, and how big change is possible through developing ‘pathways to potential’ and working where the energy is (people are energised in different ways, use it to enable the tasks they want to explore, not everyone wants to be engaged – work with those who do).

The keynote speeches by Päivi Raivio and Marko Ulvila on Day 2, focussed on the question ‘how do we engage people for change in a way that is not empowering the already empowered?’ from the perspective of art and design in a place, and from an activist perspective. Discussions followed around barriers to engagement being around people’s time, willingness to engage, and how to manage the dilemma of engagement being a long term practice with decision makers’ need to demonstrate short term outcomes.

Paper session 1

Gloria Giambartolomei, Alex Franklin, Jana Fried – Engaging with Resourcefulness and Transformation in Natural Resources Management in Wales

This session explored the policy context in Wales, and covered how processes of ‘imagining’, designing, validating and reporting are being used in a community land use project in Wales – Project Skyline. Project Skylines’ feasibility study is looking at the possibility of communities managing the landscape that surrounds their town or village and asks the question ‘what would happen is we handed to local people the means to shape their own environment for hundreds of hectares for hundreds of years?’ The community was asked to imagine the potential of their land through setting out their visions, fears, dreams and values. This then comes together at the designing stage with issues around ownership, land use, ecology, planning policy, governance options and business models to develop a community land use plan.

Ancia Cornellius – The Living Landscape Approach. Multifaceted Roles for Rehabilitation in a Complex Socio-ecological Landscape

Drawing on Theory U to help facilitate profound social and ecological change using bottom-based and top guided process, theory U was used as a building block to deliver 4 returns; natural capital, inspiration, financial capital and social capital. This involved key roles: landscape mobilisers, knowledge brokers, facilitators, business developers and landscape innovators to support and facilitate social learning and change processes with stakeholders (farmers, private landowners, businesses, public sector bodies, schools, academia and other civil society organisations) on a landscape scale. Knowledge was co-developed to identify key points for landscape transformation. Landscape mobilisers were about building trust – facilitating and understanding opportunities. Knowledge brokers facilitated a collective understanding of language and terminology. Facilitators enabled conversations with people with power. Businesses developers looked at solutions for long term sustainability. Landscape innovators made the link between research institutions and ‘learning by doing’.

Practice session 7

Anastasia Papangelou, Marta Nieto Romero – Collaboration Made Fun: Improvisation workshop for Interdisciplinary Geeks

Cross-discipline working is at the core of sustainability – both science and practice. However, collaboration for cross-disciplinary projects is often a challenge with different disciplines speaking differing languages and there is often an unwillingness to step out of comfort zones to understand each other. Humility, respect for others and a culture of constructive dialogue are essential, yet cultivating these traits and skills are not an easy task.

This practice session applied a range of improvisational techniques based on the set of principles including; always accepting and further developing your partner’s idea (‘yes and…), making your partner shine, failing happily.

Paper session 4

Clara Lizarazo, Satu Tuittila, Benat Olascoaga, Anna-Kaisa Tupala, Pira Cousin, Panu Halme – Engaging Citizens from 4 Different Places in Finland Towards Small-scale Ecological Compensation

This focussed on the question – how to engage citizens towards small scale ecological compensation actions. Responses involved methods around strengthening the human/nature relationship; having time in nature to explore and sense, exploring relationships and values around nature and what motivates action. Participatory approaches included a walk and documenting through photos what citizens would like to change or have more over and workshops to design clever, easy actions drawing from what people find relevant.

Daniele Brombai – Is Fighting with Data Enough? Prospects for Transformative Citizen Science in the Chinese Anthropocene

This session was about the potential of citizen science in China to generate sustainable transformations through enabling people to challenge institutions to drive transformational change. In the words of Rachel Carson in ‘A sense of wonder’ – once emotions have been aroused, then we wish for knowledge.

Annex – The policy context in Wales

Policy development is about drawing on a wide range of evidence to develop ideas and options to effect change for decision makers. One of those options is to develop legislation and the Welsh Government has world leading legislation for sustainable development.

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 requires public bodies to take action towards well-being goals which set a vision for action across Wales, through 5 ways of working.

The Environment (Wales) Act 2016 sets out legislation to manage natural resources sustainably through the ecosystem approach. It similarly sets out an objective – to maintain and enhance ecosystem resilience’ and is delivered through applying 9 principles. The delivery framework consists of a national evidence base – the State of Natural Resources Report, which links natural resources to well-being; a Natural Resources Policy, which sets out national priorities, and Area Statements which deliver the Natural Resources Policy in a local, place based, context. The Act also sets out carbon budgets for decarbonisation.

The Acts are designed to work together, and more information can be found here:

The Natural Resources Policy was published in 2017. It sets out place based working as one of the priorities, acknowledging the important role that it plays in supporting the delivery of the ways of working to deliver lasting change and build social capital.